Working in a laboratory environment involves daily exposure to chemicals, biological materials, and high-precision equipment such as thermocyclers used in PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) processes. While these are essential tools for scientific research, they can also create occupational risks for the skin.

According to occupational dermatology studies, skin diseases account for 30–45% of all work-related illnesses, and contact dermatitis alone makes up about 95% of these cases. Laboratory personnel—scientists, research assistants, and technicians—are particularly vulnerable due to repeated chemical exposure, frequent hand hygiene, and the use of protective gloves for extended periods.

Chemical and Disinfectant Exposure

Laboratory staff handle a wide range of solvents, acids, bases, dyes, buffers, and disinfectants on a daily basis. Continuous contact with these substances can damage the skin barrier, resulting in irritation, dryness, or burns.

For example, when preparing PCR reagents, exposure to buffers with varying pH levels or reactive agents can trigger irritation or allergic responses if proper protection is not used.

Biological Exposure

In microbiology and molecular biology laboratories, workers often deal with biological samples such as blood, tissues, or microorganisms. These increase the risk of skin infections, allergic reactions, and accidental exposure. Although less common than chemical irritation, biological skin infections still account for up to 10% of laboratory-related skin diseases.

Equipment and Environmental Factors

High-temperature equipment such as thermocyclers can produce localized heat and humidity. Combined with frequent glove use and constant hand sanitizing (“wet work”), this environment weakens the skin’s barrier function and increases the likelihood of contact dermatitis.

Frequent temperature shifts between hot and cold surfaces during PCR procedures can also lead to micro-cracks or dryness in the hands.

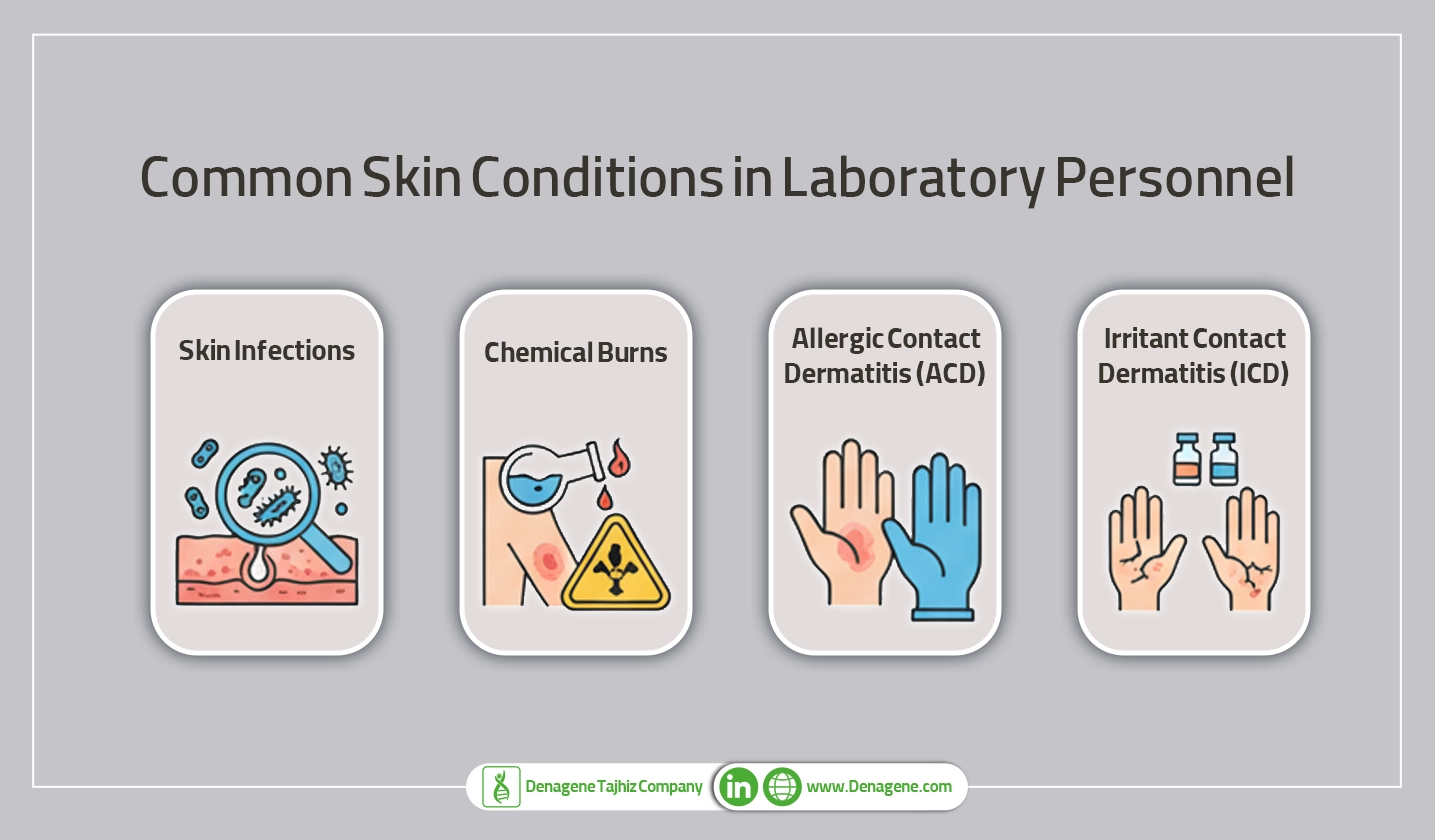

1. Irritant Contact Dermatitis (ICD)

The most common occupational skin disorder—accounting for up to 70–80% of all cases—results from direct damage to the skin by irritants such as solvents, detergents, and repeated handwashing.

Symptoms include redness, scaling, cracking, and sometimes blistering or oozing, especially on the backs of the hands and wrists.

2. Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD)

In ACD, the immune system becomes sensitized to a specific chemical (allergen). Even minimal contact later can trigger an inflammatory reaction.

Patch testing is the diagnostic gold standard. In laboratories, allergens may include latex proteins, metals (nickel, chromium), dyes, adhesives, or certain PCR reagents.

3. Chemical Burns

Strong acids, alkalis, or reactive agents can cause severe burns on contact. Immediate washing with copious water and prompt medical care are critical.

Examples include exposure to cleaning solutions or concentrated chemicals used in reagent preparation.

4. Skin Infections

Small cuts or abrasions allow bacterial or fungal organisms to enter the skin, leading to cellulitis, abscesses, or tinea. This is especially a concern in microbiology labs.

5. Other Laboratory-Related Disorders

Less frequent conditions include radiation-induced skin damage (from UV exposure), friction injuries, and acne mechanica caused by prolonged use of facial protection equipment.

Modern molecular laboratories rely heavily on PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) to amplify DNA. The thermocycler—which repeatedly heats and cools samples—is central to this process.

However, PCR workflows involve several potential skin hazards:

Together, these factors create a chronic load on the skin barrier, leading to increased rates of occupational dermatoses among PCR-based laboratory workers.

Medical History and Examination

A detailed history is essential, including:

Additional Tests

A strong temporal link between work exposure and symptoms supports the diagnosis of an occupational skin disease.

1. Elimination or Reduction of Exposure

2. Skin Care and Protection

3. Pharmacological Therapy

4. Referral and Documentation

Chronic or recurrent cases should be referred to an occupational dermatologist for comprehensive assessment, patch testing, and documentation for workplace safety reports.

Conclusion

Occupational skin diseases among laboratory scientists and technicians are common but largely preventable. The combination of chemical, biological, and mechanical exposures, along with repetitive tasks in processes like PCR using thermocyclers, places constant stress on the skin barrier.

By implementing effective preventive strategies—proper PPE, skin-care routines, and workplace education—laboratories can significantly reduce the burden of dermatitis and related conditions. Maintaining healthy skin not only protects employees but also supports consistent scientific productivity and safety within the lab environment.